|

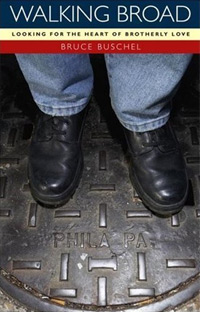

Walking Broad, by Bruce Buschel

Simon and Schuster, 2007, 224 pages

ISBN-13:978-0-7432-9284-9

Reviewed by Nathaniel Popkin

My friend Peter Siskind and I invent long city walks across city neighborhoods, time, and cultures. Or, borrowing from the author Will Self, we consider walking

out of

Philadelphia and continuing to New York—anywhere really. "How cool would that be," he says, imagining navigating the towns, highways, and strip malls of the

Northeast Corridor. (Much of his research as an historian is on the post-war development of the Northeast.) "Fascinating," I always reply and our eyes shine a

little

and then we go back to talking about the Phillies. Inventing such journeys isn't new to Siskind, who with his wife Judi Cassel, once biked across the country;

nowadays

he'll spend Sunday mornings with Leo, their son, riding across Philadelphia on "bus adventures." For example, they'll take the 48 from their house in Fairmount

to the 26

on Olney Avenue to the H in Germantown, returning on the 33. This is how both father and son have learned every Septa route, nearly every inch of their

city—and not

surprisingly each other.

My friend Peter Siskind and I invent long city walks across city neighborhoods, time, and cultures. Or, borrowing from the author Will Self, we consider walking

out of

Philadelphia and continuing to New York—anywhere really. "How cool would that be," he says, imagining navigating the towns, highways, and strip malls of the

Northeast Corridor. (Much of his research as an historian is on the post-war development of the Northeast.) "Fascinating," I always reply and our eyes shine a

little

and then we go back to talking about the Phillies. Inventing such journeys isn't new to Siskind, who with his wife Judi Cassel, once biked across the country;

nowadays

he'll spend Sunday mornings with Leo, their son, riding across Philadelphia on "bus adventures." For example, they'll take the 48 from their house in Fairmount

to the 26

on Olney Avenue to the H in Germantown, returning on the 33. This is how both father and son have learned every Septa route, nearly every inch of their

city—and not

surprisingly each other.

For Bruce Buschel, walking the length of Broad Street (an urban hike worthy of a Skyline photo essay) is deeply personal, too. If the bus adventures are a giant

inhalation (of street corners, routes, bus drivers, passengers, time together) then Buschel's walk is the equivalent exhalation, and here on 224 pages is

everything about

his native city he had to get off his chest. Buschel, the 61-year old journalist and filmmaker, grew up and lived in Philadelphia until his thirties. Broad

Street was

his street of misbegotten dreams.

At the start of Walking Broad, Buschel quotes Stephen Berg, the Philadelphia poet and founder of the American Poetry Review.

Everything stays the same is the truth of truths;

Everything changes whether you believe it or not.

Berg's wisdom is the frame for Buschel's project. And Buschel wants to accept it. He's looking for change, after all, and is effective and entertaining in

describing

it. But in the end, he doesn't believe his old city has changed—is always changing—and this is perhaps what is most disappointing about Walking

Broad.

Buschel is a clear, honest, and funny writer, which makes Walking Broad a great read.

Coming back from a Phillies game or following s successful night at Mosconi's pool hall, around ten or eleven, we'd cruise up and down this stretch of

Broad

Street and spy a tomato in a short skirt—Eliot called them tomatoes, hothouse, farm-ripened, or heirloom, anything but cherry, and never Jersey—and

Eliot would

signal her with a hissing "Pssst! Pssst!" Pushing wet air in short truncated streams through your closed front teeth made a sharp, vaguely sexual sound that

could

perforate any night. "Pssst! Pssst!" The tomatoes would walk over to the car to negotiate.

"How ya doin', babycakes?" she would ask.

"You got some time for us?" Eliot would ask back.

"You wanna go 'round the world?"

"How much for a blowjob?" he would ask.

"You a cop, baby?"

"Do I look like a cop, baby?"

"No, baby. I jest gotta ax."

Along the route south he calls his brother in California several times, calls up memories and conversations, and quotes notes and e-mails. He covers obesity, gun

crime,

poverty, abandonment, education, and the fall of newspaper journalism. He travels the Philadelphia landscape, from the Lenape to Penn, Girard to Steven Starr,

Joe

Frazier to Lew Blum, Haym Salomon to Kevin Bacon and his dad. Though he's been a New Yorker for 25 years, Buschel can get to the heart of the Philadelphia matter

with

ease, perhaps without even realizing he is doing it. He is marvelous chatting with the manager of the Earl Scheib shop, describing the service at the Chinese

Mennonite

Church, playing the fool with the Chief Operating Officer at CHOP (trying to understand how the great children's hospital can have a McDonald's), listening to a

sock

vendor describe his theology—

At the corner of Broad and Indiana, in front of a small shopping mall, I pass a chubby black dude hiding behind sunglasses and a black baseball cap.

"Socks," he says. "Six pair for five dollars."

I'm set with socks, so I just walk on by. Halfway down the block, I think maybe it's not socks he's selling, maybe a euphemism, a street code for some other

contraband,

something more imaginative, perhaps imported. What the hell.

"Socks," I ask, eyebrow raised steeply.

"Socks," says the man.

"Where are your socks from?"

"Heaven," says the vendor.

"You got socks from heaven?"

"Direct from heaven," he says.

"How did they get to you?"

"I am blessed, brother, blessed."

Buschel's prose moves quickly, moving on a dime from the street corner to the crevices of his memory. There, he often finds his mother, in a house in Logan

(since

demolished), widowed with two children, and a habit of bringing scotch to bed at night. I'm reminded here of the poet Berg's grappling with the relationship with

his

mother, which he does throughout his work, most directly in The elegy on hats. The two men share enough in common, growing up in working-class Jewish

homes in

Philadelphia with dissatisfied mothers and fathers who eventually drop dead. Buschel grew up during an ugly time in urban America. Crime, abandonment, and

poverty

skyrocketed. Traditional ties broke down once and for all. Neighborhoods changed quickly. Viet Nam left ample scars. Buschel thinks—and why shouldn't

he—that

all this was particularly hard-felt in Philadelphia, that therefore growing up in Philadelphia was somehow more brutal, potent, mind-addling than anywhere else.

But for

all Philadelphia suffered—the '64 Phillies, Rizzo, racism, MOVE—New York had the Son of Sam, the blackouts, Sing-Sing, Bronx burning. For all that

Buschel was

piddled at Girard College, priests in Boston were dementing their altar boys. Even Paris lost population. London still hadn't recovered from the war.

If you think growing up in an insecure, violent city under attack from without and within, by simpleton police chiefs and pyromaniac mayors and mad-dog media and

manic-depressive stand-ups and cuckolded uncles and the fat, unshaven newspaper dude down the corner doesn't take a toll on your soul, you are not a

Philadelphian.

But Buschel thinks decline, misfortune, and pervasive depression are the only ways to understand his city. Because of that—because he doesn't really believe

things

change (in many directions at once)—he shrouds his fast-pace jaunt down Broad Street with the usual, tired narrative frame: Philly is a rest-stop between New

York

and Washington, a "'taint," "a small town hiding as a big city," full of authentic, impolite people. Here we get the MOVE bombing, the ridiculous accent, the

failure of

our sports teams, the Philly dance of death, the post 9/11 renaissance (uh-huh, Philly only woke up in 2001. Please, Bruce). We get the usual vaguely truthful

but

suspect observations: Philadelphians don't take public transportation (Septa reports a million rides a day); Philadelphians never say, "Have a nice day" (Bruce,

no one

ever told you, "Hafa goot wun"?), we hear from Josh Olsen, a screenwriter, "The only really smart thing I ever did concerning Philadelphia was leave," "Philly is

a city

for idiots. Linear, rectangular, straight ahead." Are we supposed to forget the grid was a great act of the enlightenment or that his description would fit

Manhattan

too? Gee, I bet he wouldn't say, "New York is a city for idiots."

The frustrating thing is that Buschel makes it clear he understands. His research is thorough. He knows that what differentiates Philadelphia during the time of

his

growing up is that foreign immigration, which began declining in 1910 only began to recover in the 1980s, and slowly at that; that immigrants are the lifeblood of

American city. He understands this, implicitly recognizing the importance of the ongoing wave of Mexican immigration (immigrants as a percentage of overall

population

are now back to the 1950 level and rising). But he wants us to think Philadelphia hammers everyone who comes here into a kind of dull daze, capable of spelling

E-A-G-L-E-S in unison a little else. This is authorial murder: trampling a million little narratives into one.

That's his prerogative, I suppose, it's his exhalation. I just wish he'd held his breath a little more and written with his eyes and ears instead.

–Nathaniel Popkin

nrpopkin@gmail.com

For more on Walking Broad, visit your local book shop -- how about Joseph Fox Book Shop or Robin's Bookstore?

|