7 March 08: The Possible City:

One-City Art Movement, Open to Everyone

|

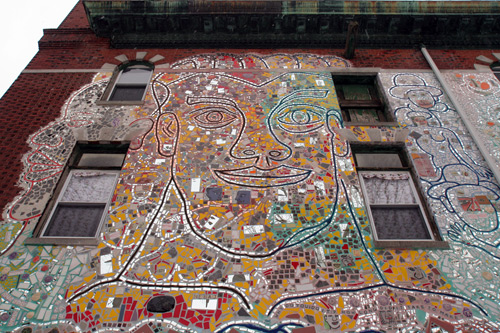

by Nathaniel Popkin March 6, 2008  Michael Taylor, who came to Philadelphia from London, has a bright round face and greedy eyes and a kingly accent that's like a splash of lime across our dreary patois. If you've been to see Frida Kahlo at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (PMA), it's Taylor's voice that guides you through the exhibit. Taylor, the Muriel and Philip Berman Curator of Modern Art, delivers a lecture, "Frida Kahlo revealed," this afternoon at 3. Taylor at mid-career is in the zone. He organized the wildly successful 2005 Dalí retrospective; his exhibit on the American artist Bruce Nauman has been selected to represent the US at the 2009 Venice Biennale; and he's now at work on the first US retrospective of the Armenian Arshile Gorky. What's more, his wife, Sarah Powers, an adjunct professor of art history at Moore College of Art, is about to give birth to their first child. But one of the most moving currents in Taylor's life is his friendship with the perspicacious artist Tom Chimes, whose anthology, "Adventures in 'Pataphysics," he organized last year. It's easy to see why Taylor has befriended Chimes, who is 86 and lives on Washington Square. Both men revel in the connections -- among artists, ideas, events, and eras -- that swirl around, infect, and take meaning from Philadelphia. "You see," says Chimes, smiling, "this is a very important place." We're sitting at the end of the long, communal table at Zeke's, the Fifth Street diner where the two men meet regularly for lunch. Powers and Claire Howard, Taylor's research assistant, have also joined and Zeke's is filled -- with dilettantes, lawyers, grandmothers who pocket packets of Sweet 'n Low. Chimes, who wears a red plaid shirt, navy knit tie (the kind with the square end), and v-neck sweater, speaks in a measured, nasal tone, one that is sweet, almost hallucinatory. A BLT sits on his plate untouched, but Chimes doesn't seem to mind. He's having too much fun reciting a speech he gave February 2 to the Hellenic University Society of Philadelphia. In his speech Chimes reminded the audience of the power ancient Greece once had over him. At age 13 and attending a Greek school on 57th Street in West Philadelphia, he noticed a frieze, which he later learned represented a scene from the Aeneid. Interpreting that frieze led him into the imagined world of Ulysses. The key notion in his speech -- indeed, the idea that penetrates all his work -- is that time is as pliable as any other cultural input. Or, as Chimes says while gazing across the table at Powers -- and I am paraphrasing -- "as [the French intellectual and major Chimes influence] Alfred Jarry writes, 'we should be able to travel through all future and past instants successively . . . we shall see that the Past lies beyond the Future'." Much is being made right now of Philadelphia's mounting art scene. As Melissa Dribben reported a couple of weeks ago in the Inquirer, for the past five years artists have been descending -- in ever-increasing numbers -- on Philadelphia. Do-it-yourself (DIY) galleries, collectives, and social networks are producing a new energy -- or a recombinant strain of an old energy -- one that is palpable in certain parts of the city. As seen in my recent exploration of Norris Square, we assign artists, who Chimes calls seers, special powers to transform the city. Taylor says to understand this current moment we have to travel back to the 1960s. Marcel Duchamp came here in 1961 for a panel discussion at the Philadelphia Museum School of Art (now UArts) and said prophetically, "Where do we go from here? The great artist of tomorrow will go underground." The Philadelphia art scene since then, according to Taylor, has been that underground, the antithesis of market-driven New York. And right now, it feels, as Willem de Kooning said of Duchamp, like a one-city art movement open to anyone. "The art story is the same as the city story," says Genevieve Coutroubis, the West Philadelphia photographer who runs the Center for Emerging Visual Artists' (CFEVA) regional community arts program. Coutroubis, who spends five or six weeks a year in Greece making luminous, scorching black and white street photographs, says "New York is New York and LA is LA." But "It's hard to replace what we have," she tells me, meaning the mixture of affordability, major institutions, art schools, art-making clubs, and support organizations that make it possible to "live as an artist and experiment." Time-traveling with Tom Chimes, we might discover that Philadelphia artists since the 18th century have been trying to do just that but have found themselves forced to interrogate a city skeptical of the usefulness of culture. Since Charles Willson Peale set up his museum, Philadelphia artists have struggled for markets, for recognition, for impact.  In 1813, a group of promising and influential painters attempted to define the range and style of American art by forming a sketch club. But after a year or two, several of them, including Peale's son Rembrandt, gave up on the place and left for Baltimore, London, or New York. The ones who stayed struggled to capture the public's imagination. As for all the present DIY versions of the 1813 sketch club, will they too dissolve in frustration? Will the most promising fail to find a local audience and move on? Or will the richly-variegated art-making take hold in the post-industrial landscape? Will art become yet another element of our towering knowledge sector? Will artists' energy and instinct to create help Philadelphia overcome its seemingly intractable problems? Is it even possible to capture a counter-culture movement for economic ascendance or community development? If you try -- say by creating a city bureaucracy to promote art -- are you undercutting the power of the art you're trying to promote? I put some of these questions to Roberta Fallon and Libby Rosof, the editors of the effusive, ambitious, and comprehensive Artblog, when we met last week at Old City Coffee on Church Street. Since 1998, Fallon has followed the art scene in the Philadelphia Weekly; "Columnizing is what got us started," says Rosof. "In 2003 there wasn't the level of excitement. We were excited, people were making things, the proverbial tree falling in the woods." The two, who met in 1986 watching their kids play at the Greenfield School playground, have been making and talking art together for years. "We're just a pair of old intellectuals," says Rosof, who laughs. She is outgoing and funny, amusingly irreverent. Fallon, who grew up in Milwaukee and attended the University of Wisconsin-Madison during its 1960s activist hey-day, is quieter but no less enthusiastic. Her schoolmarm appearance belies vision, wit, and sharp analysis. And no one yet has challenged their hold on the territory. (FYI, dames Libby and Roberta will spend this evening, First Friday, attending two lectures at PAFA, one on the FBI and art theft and the other a discussion with Rob Matthews, who makes wondrous photo-realist drawings in graphite.) According to Rosof and Fallon, there have been recent structural changes -- beyond relative affordability and proximity to New York -- that are fueling the acceleration of the art sector in Philadelphia. Pew increased the amount of its Fellowship from $50,000 to $60,000; and a handful of organizations like CFEVA and the Philadelphia Exhibitions Initiative are making it easier for artists to reach the public. Most critically, Philadelphia's art institutions -- from Drexel to Tyler, Moore to UArts, PAFA to Penn -- have added fields of study, reworked curricula, and begun encouraging students to exhibit work. They've hired better and more ambitious curators and faculty who in turn put on more challenging shows. "The kids are no longer fleeing," says Fallon. But what are they making? Autobiographical, angst-ridden work, paintings as objects with references to ecology, pop culture, guns, and videos, according to the art bloggers. "Video is where art is moving," says Rosof and Fallon agrees. She says video, with its potential for narrative and drama, reaches a large audience. "Everyone uses YouTube," muses Rosof. "Let me go out on a limb," Fallon concedes, "the art [the young artists are] producing is not ground-breaking, [in Philadelphia] there's not a sense of blind ambition and drive." For her part, Coutroubis of CFEVA says because Philadelphia allows artists to experiment, the quality and range of work is high. And CFEVA's emerging artists aren't necessarily young. In fact, two rising stars she points to, Mark Khaisman and Julia Stratton, are older artists whose work is redefining the range of their media. Khaisman, whose show at the Woodmere Art Museum ends on Sunday (he was chosen from the 25 artists who completed CFEVA's intensive program this year), is a small man with three kids who grew up in a tiny apartment in Soviet Moscow. He was trained as an artist and architect in Moscow, but says "I just like drawing." Khaisman speaks softly and with a thoroughly evocative accent. He giggles because he "draws" with packing tape. "I like limitations," he says referring to the simplicity of the medium, which conversely has freed him to explore popular themes of sex and violence as an old master speaking in a contemporary idiom. Now magazines and film crews from Japan and Germany have come to Philadelphia to listen.  Stratton is the PAFA-trained sculptor who gained attention last year for her show at the

Delaware Center for Contemporary Arts in Wilmington. A Requiem for a Soldier, a series of bronze sculptures that quietly confront our mediated

notions of war, was influenced by Mozart's Requiem. She's at work now on Music Box, a large scale piece that when finally installed at the Kimmel Center

could alter our notion of public art. It's an idea that is influenced by and incorporates the music of the turn-of-the-century Russian composer Alexander

Scriabin. Scriabin had synthesia, the ability to see color in musical notes. The sculpture is a twenty-foot-tall box with a surface whose video images

and colors can change along with music that descends from a piano on top (Stratton recalls sitting under the piano as a child while her mother played).

We the audience get to sit inside the music box as music quite literally transforms the world around us. Stratton says the project, in the conceptual

stage, would be mounted for the Kimmel's tenth anniversary.

Stratton is the PAFA-trained sculptor who gained attention last year for her show at the

Delaware Center for Contemporary Arts in Wilmington. A Requiem for a Soldier, a series of bronze sculptures that quietly confront our mediated

notions of war, was influenced by Mozart's Requiem. She's at work now on Music Box, a large scale piece that when finally installed at the Kimmel Center

could alter our notion of public art. It's an idea that is influenced by and incorporates the music of the turn-of-the-century Russian composer Alexander

Scriabin. Scriabin had synthesia, the ability to see color in musical notes. The sculpture is a twenty-foot-tall box with a surface whose video images

and colors can change along with music that descends from a piano on top (Stratton recalls sitting under the piano as a child while her mother played).

We the audience get to sit inside the music box as music quite literally transforms the world around us. Stratton says the project, in the conceptual

stage, would be mounted for the Kimmel's tenth anniversary.One night last week, I head over to the warm South Philadelphia house Stratton shares with her husband, the sculptor Shane Stratton. Shane, who calls his own work Etruscan, has expanded Julia's studio, which is on the ground floor of their corner building, and they are having a party to christen the new studio. They are also saying goodbye to the talented silversmith Wally Gilbert, who had been staying with them and sharing the foundry the two Strattons use on Frankford Avenue in Fishtown. The foundry is a magnet for metal sculptors. "Artists love it here," says Julia Stratton, who has strong sculptor's hands and dark auburn hair. She means that the city affords people the opportunity to work full time as artists. Shane, who grew up in the country, calls himself a "city boy." The city, he says, is engaging. "Art is in the exploration," adds Julia. But it's also in the community, the sharing of resources, of time, technique. Shane and Julia met as high school students participating in the Governor's School for the Arts (where Julia convinced Shane to take sculpture and where they learned how to cast), and in some ways they exemplify the Philadelphia artist's trajectory. They both attended PAFA, where Shane teaches once a week, and while they follow quite separate career paths, they're supported by a rich network. "We couldn't do what do somewhere else," Julia says. Fallon and Rosof are drawn to this social part of the art scene; they see so much collective energy in the DIY experimenters at 1026, Crane, Flux, !, Little Berlin, Circulean, and My House, places instilled with music as well as visual art, that they're willing to forgive shortcomings. "It's entirely possible that DIY galleries won't last more than a year or two," says Fallon. "That's life," concludes her partner. The larger point is that the very young artists are worth paying special attention to because they are establishing dynamic networks, pushing each other intellectually and artistically (including the creation of boundary-busting, synthetic music), buying one another's work, and, from Kensington to South Philly, engaging in the life of Philadelphia's neighborhoods. "Art is happening everywhere," says Coutroubis, whose organization supports artists within 90 miles of Philadelphia. "This is what is important about Philadelphia. Artists live and work in every inch of the city." "Philadelphia has always been affordable and a relatively easy place to live, so I'm very dismissive of re-saying this is a better time," says Jeff McMahon, the Philly native and graduate of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, whose cerebral and sometimes realist paintings explore the distance between artist and audience. McMahon, who wrote graffiti in El stations as a teenager, sees an art world ever-more beholden to the wealthy and the life of the artist circumscribed by relatively few opportunities to break out. "It's like fucking playing the lottery, that's what an artist's life is like," he says, his voice deep and words deliberate, and then he slowly corrects himself. "The artist's life is not a horrible thing, it's incredibly beautiful." The difference, he explains, is between the artist who strives to be a celebrity -- "all artists want to break out, passionately, desperately" -- and the art-maker, who loves to think, invent, produce. That discrepancy -- really a brutal tension -- shapes the art scene in Philadelphia. Philadelphia artists are relatively lucky. Given the plethora of institutions, many work in regular jobs within the arts and academic sectors, jobs which pay enough and allow the flexibility to be productive art-makers. As Roberta Fallon puts it, "They live partially above and partially under ground." But in a global art market that embraces youth, style, and surface, and a local market that has relatively few commercial galleries, the difficulty in breaking through forces many to invent novel and only sometimes rewarding ways -- outside of gallery and museum -- of connecting with an audience. Rembrandt Peale's frustration carries clear across two centuries. "We're always giving stuff away," says Rosof about the paintings she and Fallon make. Artists commonly sell to each other and parents, barter, and open eponymous galleries, and work on commission. McMahon invented the Shared Picture Project, the exchange of 100 paintings that had been sitting in storage for 100 pictures of those paintings. The idea originated with the desire simply to empty the storage closet. What good was all that art if no one could see it? But the project has evolved into being a complex communication between the art-maker and audience, ultimately forcing participants, each of whom is required to make a photograph of the painting, into art-maker herself. "We're so used to fascism in art -- any plurality in art-making is ambiguity -- but no, here is process, not the single voice [of the artist]," he says, noting that all of a sudden, the audience is forced into a new role, that of confronting the fear of having the work not be accepted. Just as an artist submitting work to a gallerist, many participants have sent several photographs with the hope that one would be worthy. McMahon has also painted about 20 "place paintings," usually neo-impressionistic rural snapshots, which can be removed from the canvas (the canvas is taped before the paint is applied) and then affixed to a wall, sign, or other piece of street furniture (try to find the place painting at 9th and Locust). It's "invisible art," art in the public sphere that is meant to be ignored. "I've discovered some magic; it's poetic like a tragic play," he says, "beauty torn from its home, lost then never noticed. But I know it's there." Public art in Philadelphia usually declares its presence and tells us just exactly its intent. The Mural Arts Program makes beauty out of rubble, literally. Though the best of his work is narrative, Isaiah Zagar's fantastic murals tell us what to believe: Art is the center of the real world.  Though there are about a dozen public art guardians in Philadelphia (the City, Septa, PHL, etc.), most public sculpture is the responsibility of the Fairmount Park Art Association (FPAA), begun with progressive intent in 1872, and led since the early 1980s by Penny Bach. She and I meet in the conference room of the FPAA; there we're surrounded by posters of past projects and art books and magazines, including one on the sculptor Martin Puryear, whose MOMA retrospective just ended and who built Pavilion in the Trees near the Horticultural Center in Fairmount Park. Bach has strawberry blond hair and wears black cat-woman glasses and speaks with a Philadelphia accent. She's from the same West Philadelphia that produced Sam Katz and Judith Rodin; "Philadelphia has been good to me," she tells me -- and indeed, Bach has put in her time. She spent her early career teaching art at Bieber Junior High School, where she had attended, and then was hired to help establish the Parkway Program. Parkway, by the way, was a forward-looking experiment in pedagogy. The rather radical idea was an open campus: the Parkway and its institutions was the high school; all that art and science was the basis for the curriculum. (Not surprisingly, Parkway was attractive to suburban families, whose children were allowed to attend in exchange for city children attending suburban schools.) In 1872, FPAA was no less radical. Bach explains that its founders weren't merely the elite, but rather a diverse lot of citizens who thought that the industrial city was ugly, fragmented, and uncultured. "Before the Parkway, the Museum, the Planning Commission, the Art Commission, this really was city planning," Bach says. Art would be thoughtfully selected, intentional, and integrated into the growth of the city in every possible way. And indeed the FPAA anticipated the invention of American city planning (it also pre-dated the Municipal Art Association in New York), and was so highly-regarded that the arm of the Statue of Liberty appeared here first, as part of the city's Centennial Exposition. The FPAA established a broad context for art. Bach says this is why Philadelphia has so much work by foreign artists. Bach is nearing the completion of her second major project. The first, Form and Function, produced Puryear's gracious Pavilion in the Trees as well as Rafael Ferrer's El Gran Teatro de la Luna in Fairhill Square (since removed), Siah Armajani's seating at The Fleischer Art Memorial, and Jody Pinto's Fingerspan in the Wissahickon:  Begun the 1990s, New Landmarks was designed to respond to community needs. Whereas Form and Function asked artists to find suitable sites for their work, the current project reverses the trajectory, engaging communities in the process of creating public art. Bach tells me, "We started by asking communities what they wished to leave behind." Negotiation, she says, "yields results." As art transforms the city, the city transforms art. The project has commissioned Diane Pieri's Manayunk Stoops, Ed Levine's Embodying Thoreau, and Pepón Osorio's I have a story to tell you . . . in Congreso's new headquarters. Underway is A Century of Labor in Elmwood Park in the Southwest and Church Lot in North Philadelphia. The FPAA and Project HOME commissioned artists John Stone and Lonnie Graham, who is also acting associate director of the Fabric Workshop, and novelist Lorene Cary to create a sacred space on the vacant lot left by the fire at St. Elizabeth's church at 23rd and Berks. St. Elizabeth's was an icon in this neighborhood of rather proudly-restored 19th century row houses with elaborate brick and terracotta work, bracketed cornices, and little wooden "balconies" and awnings that abut the rebuilt Raymond Rosen project. It's a cold morning when Graham, Stone, and I meet, and we sit for a while inside Stone's SUV. Edward Hopper's Early Sunday Morning stands in flesh and blood -- bricks and mortar -- just across Berks Street. The early sunlight crosses the vacant lot and warms us. Outside it is quiet. Though this small section of central North Philadelphia remains intact, much of the surrounding streets are empty; they suffer invisible ruin. John Stone is one of those people you see all the time on the streets of Philadelphia, and so we recognize each other at once: Bella Vista dads. Stone, a sculptor, is tall and wears a terrific head of dreadlocks. Graham, bearded, also a dad of small kids, is soft-spoken and kind. He comes from the town of Seldom Seen, in southwestern PA. "It's a very basic idea," he says, "to give people ownership over where they live and what they do." But Graham, who was a Pew Fellow in 2002, sees a special role for artists in the community-building process. "Artists -- painters, photographers, poets--have a valid, tangible role as creative problem solvers, a useful role. It's something that makes a lot of sense." Stone calls giving regular people a say in public art "psychological ownership. It's where a lot of artists forget. It's an ego issue." And so the sacred space they're planning for the Church Lot (as it is called), as many of the pocket parks that Stone has planned in the neighborhood, is designed and built by kids, old people, and teenagers, teaching skills and landscape design. Stone built the park before the sculpture project was proposed (final designs are now complete). The project also includes a kind of re-sanctification of a luminous room inside the still-standing rectory. The renovated space, which includes a white oak table built by the sculptor Doug Mooberry from a 300 year old tree, as well as a frieze of text from neighborhood oral history and large format landscape "portrait" photographs of the neighborhood taken by Graham, will be used for community meetings. As a repository, it will also house the oral and material history of the neighborhood. Stone goes on to explain that foreclosure and abandonment have left the neighborhood with vacant properties that no one else will address. "The community is required to deal with it," he says. But the St. Elizabeth's fire, which seemed suspicious, left a brutal scar and neighbors were left to mourn. The artists' response is sculpture of galvanized and stainless steel that, according to Graham, "will allow access to the [sacred] idea that remains about this place, a physical interaction with it." Bach believes the strength of the work lies in the trust between the artists, whose ideas are avant-garde, and neighbors, who she says, invest the work with meaning. The collaborative process, what Bach calls a "little marriage" is a community-building feedback loop. As Stone and I leave the rectory, we pass Helen Brown, the community activist who is spearheading the project. As if on cue, Brown grabs Stone's coat, hugs him warmly, and plants a loving kiss on his cheek. "What's really meaningful that's going to occur is local," says Daniel Dalseth, the anomalous director of Pageant : Soloveev, the three year old gallery in Bella Vista. He means that art is a necessary antidote to globalization; it gives real voice to people. The Philadelphia art scene is just that. "International art is so much about fashion," he explains while making us coffee in the open living space above the gallery. "Sometimes it's hard to distinguish between Italian Vogue and Art Forum." As we chat, I notice a black and white photograph of Frida Kahlo and Diego Rivera on the refrigerator. Dalseth was in Mexico City last summer, where he saw the original -- and larger version -- of the current PMA show at Bellas Artes and went to the Blue House in Coyoacán. In the photo, which seems to be the basis for Frieda and Diego Rivera (1931), Rivera appears improbably huge, Frida impossibly small and slightly contorted. Laughing, Dalseth and I struggle to comprehend the proportions. Those proportions (Frida called Diego the elephant and herself the dove) were clearly on her mind. Rivera and Kahlo soon traveled to the US. In Self-Portrait on the Border Line between Mexico and the United States and My Dress Hangs There, two of my favorite paintings in the show, Kahlo feels the crushing weight of the American industrial machine. In Self-Portrait with a Mexican flag in hand -- and unlike so many artists of the day who were drawn to New York and brash American culture -- she makes her choice, aligning herself with the Mexican iconography and nationalism that would so influence her life and work.  Ultimately it's that forceful and particular localism that makes her work -- and her persona -- so desirable today. Like so many artists, she turned herself and her surroundings into a lifelong art project, a "little marriage" of place and vision. In her hands, the typical middle class house of her youth became the Blue House, which itself bore witness to and reflected the currents of the day. Dalseth, who is a painter and sculptor and who also teaches art at Dartmouth College, says "I'm trying to turn my own environment into a fantastical one -- what I want to be surrounded by, what I want to experience. I want the public spaces in this building to reflect my desire for what's not experienced [in the wider culture]." While his five-year-old son Lucien builds a Lego airplane upstairs (and visits us occasionally so his father can check on progress), Dalseth, who wears a sweet smile and hoop earrings, shows me around the building -- from the gallery's office, a Seussian vertical fort built into the wall, to the roof terrace where in the long distance Comcast Center shimmers steel gray, to the small alley below that would be a garden passage. Dalseth is assembling found objects -- "it's so easy in Philadelphia" -- into something artful that isn't about art, that expresses connections and tells stories. He imagines the Soviet Union post-revolution and pre-Stalin. Artists were put in charge of the bureaucracy; art was to be injected into everything. "I think what we're talking about is sort of a utopian idea," he says and smiles sheepishly. "I'm prone to daydreaming." Clear across town I sit in the crowded, smoke-stained living room of Joseph Tiberino, who more than any Philadelphia artist has embraced the easy play of the Philadelphia streetscape into his art and life. Tiberino is the living reflection of both the Mexican muralists and the visionary Philadelphia art-makers and impresarios like Charles Willson Peale. His compound, which incorporates five houses and nine yards in Powelton Village, is as much like the Blue House as anything in Philadelphia might be and Tiberino's life -- his wife, the painter Ellen Powell Tiberino, suffered 14 years with cancer, ultimately painting from bed -- combines art-making with celebration and social activism. The historian Steve Conn says that there have been only two family dynasties in American art, both Philadelphian, the Peales and Wyeths (three, if including sculpture, you count the Calders). And then there are the Tiberinos. "The kids do what I do. They grew up with a mother and father doing artwork all the time," he says, speaking slowly with a Kensington accent. Peale named his sons Rubens, Rembrandt, and Raphaelle; Tiberino Leonardo, Raphael, and Gabriel. Raph and Gabe are working painters, as is their sister Ellen, named for their mother, the PAFA-trained figurative painter whose defiant art and life inspired the family's house-museum. The courtyard -- that assemblage of nine yards -- is an undulating space filled with sculpture, a bar, a tree house, and found objects. Joe and Gabe's allegorical, figure-filled murals enclose the space. Near the entrance is a mural Tiberino painted about the MOVE bombing, which was deemed offensive to Mayor Goode and removed from Temple University, where it had been installed.  Sitting in the Tiberino house, it's impossible not to feel the presence of the Mexican muralists. (There's an enormous Mexican Mural Painting on

the shelf and a faded Mexican flag draped over a table and a small chapel with a painting of Ellen nursing Raphael in the center.) "To tell you the truth

I never thought [Kahlo] was very good. [Rivera] was the one, you know," Tiberino says, smiling wryly. He wears a black-brimmed hat and thin gray beard

and mustache; he stands close and grabs my arm for emphasis. Tiberino's work seems to combine Rivera and Siqueiros, the Mexican fabulist he adores most

of all.

Sitting in the Tiberino house, it's impossible not to feel the presence of the Mexican muralists. (There's an enormous Mexican Mural Painting on

the shelf and a faded Mexican flag draped over a table and a small chapel with a painting of Ellen nursing Raphael in the center.) "To tell you the truth

I never thought [Kahlo] was very good. [Rivera] was the one, you know," Tiberino says, smiling wryly. He wears a black-brimmed hat and thin gray beard

and mustache; he stands close and grabs my arm for emphasis. Tiberino's work seems to combine Rivera and Siqueiros, the Mexican fabulist he adores most

of all.Tiberino takes me across the courtyard and into one of the houses that fronts on Spring Garden Street. There we pass his tragic-comic painting of Pope John Paul, Che, and Castro and into a salon filled with his wife Ellen's work. I'm staring at what is clearly a charged piece, haunting and alive, a face in fiery pastels. Tiberino tells me Powell-Tiberino made the picture from bed very near the end of her life. She had been in a coma for months; when she emerged she told her husband, "I've been on a long journey." "OK, let's go home and you can paint it," he replied. But the painter grabs my arm again. He's eager to show me his bedroom and studio, just being finished. It is there, illuminated by midwinter's bright, diffuse light reflecting pure white walls and the calm of lima bean green of the woodwork, and a 1920s gold fountain from a South Philadelphia funeral home, and the wood sleigh bed, and the Madonna, and a trio of nudes floating above the ocean, and mottled Plane trees and the black and gray sky outside the window, that the aging artist looks like a giddy child. "This is why I like it here," he says, framed like a portrait in the middle of the room. "It could be anywhere," he declares, reciting the artist's conceit of self-invention. It's possible to imagine that artists are a kind of societal avant-garde. They anticipate the future, break obsolete and arbitrary boundaries, forge connections. Chimes would say artists gaze back and forward at once, and what we ascribe to the future also colors the way we imagine the past. Thus, Fallon and Rosof, and many others, see in the hordes of young artists the same spirit of nation-building that so infused Rembrandt Peale and his peers, the desire to make something out of nothing. It's a powerful desire, one they believe is transforming Philadelphia, one artist compound, collective, and corridor at a time. Fallon and Rosof also believe that in order to make something of all this initiative, City Hall needs to respond with policy. Their Kisses for Mayor Nutter campaign's goal is to establish a city office of Arts and Culture. Rosof dreams of more concentrated art districts with special transportation between venues. Dalseth speaks about tax incentives for art-related businesses, most of which are small and easily undone by the double whammy of the business privilege and net profits tax. But Hilary Jay, who directs the Design Center and oversees Design Philadelphia, thinks art and design has to be intrinsic to the way we build the city. "It's a question of the ease and joy of everyday life. We have to have lighting," she tells me as we chat in her office on Henry Avenue. "So what is that lighting going to look like? Design is the bedrock of all things." Jay's idea is not to hope that people will visit the Design Center to learn this, but instead to have design intervene in the everyday life of the city. "Art in the urban landscape is at an architectural scale," says the gallerist Dalseth. That idea is the basis for Qb3's project, the Parking Intervention, which Jay thinks will be the highlight of this year's Design Week, October 16-22. The plan is dazzlingly simple: use temporary art installations -- the repossession of land now used for street parking for other, more inspiring activities -- to alter our conception of the meaning and possibility of public space. We might imagine Tom Chimes in Alfred Jarry's time machine -- capable of penetrating all bodies, including, we are to presume, the sacrosanct institution of the parking space. Let's all climb into that machine, for perhaps the green, car-less city of the future will be a lot more like the human-scaled democracy of ancient Greece. –Nathaniel Popkin nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com For more on The Possible City, please see HERE. For Nathaniel Popkin archives, please see HERE, or visit his web site HERE. |

|

• 24 Feb 08: "Too late for the streetscape? • 15 Feb 08: "It really could be something." • 18 Jan 08: Estuary of Dreams • 11 Jan 08: More than shelter • 10 Jan 08: Nature's balance • 6 Dec 07: Snake uprising • 4 Dec 07: A Junction that ought to be • 6 Nov 07: Around the Mulberry Tree we go • 29 Oct 07: Wondering about wandering • 5 Oct 07: No other way • 21 Sept 07: Here is the Possible City |