29 April 08: The Possible City

"This is not pie-in-the-sky"

|

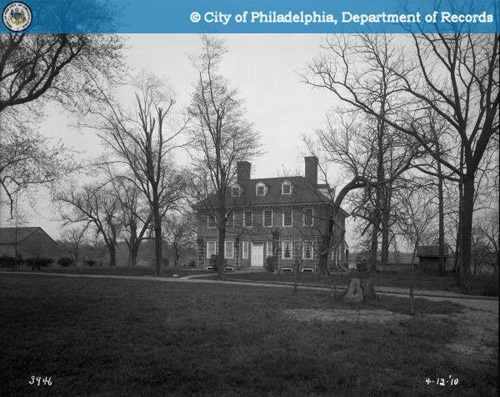

by Nathaniel Popkin April 29, 2008  Image of Stenton Park and mansion from City Archives, taken 12 April 1910. Collection ID: Public Works-3946-0, accessed at PhillyHistory.org today. Stephen Hague stands on the open back porch of Stenton, the modest English estate built in 1730 by James Logan. Logan, a polyglot Quaker, managed William Penn's colony, negotiated with Native American leaders, and grew Pennsylvania's first substantial library. Hague has been Stenton's executive director for seven years. He has sandy hair, and an easy but precise demeanor. His diction is slow, careful, his words modest. But after spending an hour on a luminous April morning discussing the framing of history -- its uses, limits, challenges, and hopes -- in the context of uncertain North Philadelphia, his diction has quickened. It isn't history that has excited him. Rather Hague seems inspired imagining a future for Nicetown and Lower Germantown. "There is a lot of opportunity here," he says then pauses. "And a lot of opportunity for missed opportunity." Stenton sits on a small parcel within a park and playground managed by Philadelphia's Department of Recreation. Stenton's three acres (shrunken from the original 500), are separated from the recreation center by a fence and maintained by the National Society of the Colonial Dames of America in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, which took over the property in 1899 as one of the nation's first house-museums. The house was never severely altered from its original configuration so it looks and feels much as it did in the middle of the 18th century. Indeed, one of the pleasures of Hague's tour is the realization that the rooms don't use electric light. As we come to a dark room, Hague enters first and opens one or two shutters, drawing light inside. Logan's 2,681 volume library, so critical to the intellectual development of the New World, was in a large second floor space that was also used for bedrooms. Logan left the books to the City of Philadelphia and today they are in the collection of the Library Company. There is only one surviving bookshelf (of possibly 20) on display. Yet the room in its raw proportions speaks. "This is what we call 'the wow moment'," says Hague of the room's power to articulate the combination of Quaker modesty and ambition that was so intrinsic to the formulation of America. This sort of magic is why we visit a place like Stenton. What's interesting is that the magic isn't produced by an historical purity. Despite what Hague calls the site's high level of "authenticity," Logan's library, for example, is interpreted in part as a pair of 19th century bedrooms; the formal garden is a 20th century Colonial Revival interpretation of an 18th century plot (Stenton hosted the inaugural meeting of the Garden Club of America); the wild hyacinths that adorn the lawn merely suggestive of a more graceful period. Stenton, in the brochures one of the earliest American colonial estates, is really a window onto almost three centuries of change. The view through the window includes a neighborhood mostly built between1880 and 1920 for skilled factory and railroad workers and foremen that today fits the archetype of urban decline. "How do you think about an historic site in a deflated part of the city?" was a question Hague was asked to consider when he took the job. "Stenton was widely regarded as a special place in Philadelphia," he says, "but at the same time there is a big fence around it -- a house built by a white man who had enslaved Africans living there." Hague's first response was to reevaluate the history told at Stenton; curators have since begun to amplify the story of women who lived there, particularly the early Philadelphia historian Deborah Norris and Dinah, a freed slave who is credited with saving the house from destruction during the American Revolution. The next step was to reinforce ties to the community. A Pew-funded grant from Heritage Philadelphia enabled the development of the History Hunters Youth Reporter Program, a collaboration of Stenton and Wyck, Johnson House, and Cliveden in Germantown. With the goal of making local history relevant to neighborhood children, History Hunters uses Germantown's demographic history, streetscape, public places, and historic houses to teach writing, math, history, business, and critical thinking. History Hunters led to further collaboration with other historic sites; among the 14 organizations that comprise Historic Germantown Preserved there is as Hague notes, "an incredible richness, the capacity to tell all kinds of stories." Collaboration also creates economic power. "Historic sites are devices," he says, assets that until now haven't produced an ample return to the neighborhood. So Hague has committed Stenton to an active role in neighborhood planning, much of which revolves around the intended $20 million renovation of the Wayne Junction regional rail station (as I reported in December, the station project is the centerpiece of a concurrent transit-oriented development study being undertaken by the City Planning Commission) . "For us, [really good] public transit would be terrific," he says. One look at a city map tells why. In addition to Wayne Junction, three blocks away and served by every regional rail line but the R6, Stenton is served by two Broad Street Subway stations and the most-traveled bus line in the city, the 23. Accessibility isn't at issue. Rather, of course, it's the perception and reality of decline and crime (there were three homicides in the vicinity of Stenton in 2007 but none directly between it and Wayne Junction).  Safety, above all, drives the station renovation, says Septa project manager Rusty Acchione, a veteran agency engineer who oversaw the Wayne and Gulph Mills station renovations. Acchione, who grew up in Germantown, is gregarious and straightforward. He wears a Villanova class ring and neatly trimmed hair. He explains how his view of the project changed when standing on the station platform he witnessed a murder just below near the entrance to Septa's Roberts Avenue maintenance yard. "The neighbors are telling me, 'We love our station, but we're not comfortable using it.' We want people to use the station." Thus, in addition to making Wayne Junction ADA compliant and installing an elevator, raising the "inbound" platform, integrating the "outbound" R7 platform, renovating the stationhouse and ticket office, Acchione wants to make the five station entrances and the walkways to the platform feel safe. That means cutting four to five foot site lines, improving lighting, and in the case of the Germantown Avenue entrance, removing the historic headhouse, a brick and stone building with carved relief and terracotta tile roof. Acchione's hope is that by removing the headhouse, he'll vastly improve the experience of entering the station; it will feel safe. And, he says, where possible Septa will re-use parts of the building throughout the station renovation. The engineer also justifies his approach by citing the cost of renovating the headhouse, which he puts at $750,000. "What can I do for the station with that money?" "But," he continues, "I understand [preserving the headhouse] is a preference." Jennifer Barr, the city's liaison to the station project and the lead planner on the Germantown-Wayne Junction transit-oriented-development study, thinks that demolition of the headhouse is the wrong approach. "I suppose removing the head house would add to the perception of safety for passengers entering the inbound tracks from Germantown Avenue," she says. "But is that worth it? The walk up the stairs will still be dark and partially enclosed, just like all the other entrances. My main purpose is to reflect the needs and desires of the community. At this point, preservation, rather than demolition, is the community's consensus." Noting that the station is listed on the National Register of Historic Places, Stephen Hague agrees. "There's lots of ways of addressing safety and security besides knocking down a beautiful building." Hague sees the headhouse as an opportunity -- potentially to bring retail life to the station -- one which is irreversible once the wrecking ball arrives.  Acchione thinks retail on the station platform, raised high

above street level, would be a difficult challenge. (Barr and community leaders are exploring the idea of placing vendors on the Windrim Avenue sidewalk in front of the

station. Although the city has agreed to repave the sidewalk, it is owned by the railroad CSX, which hasn't returned Acchione's calls.) But his idea of using parts of

the headhouse seems a stretch. Careful demolition is expensive. Moreover, though he says Septa builds to last, the agency is incapable of constructing anything as

elegant or graceful as the current headhouse. Recently erected headhouses, including one at 30th Street Station, are shamefully, almost laughably, poor. Acchione thinks retail on the station platform, raised high

above street level, would be a difficult challenge. (Barr and community leaders are exploring the idea of placing vendors on the Windrim Avenue sidewalk in front of the

station. Although the city has agreed to repave the sidewalk, it is owned by the railroad CSX, which hasn't returned Acchione's calls.) But his idea of using parts of

the headhouse seems a stretch. Careful demolition is expensive. Moreover, though he says Septa builds to last, the agency is incapable of constructing anything as

elegant or graceful as the current headhouse. Recently erected headhouses, including one at 30th Street Station, are shamefully, almost laughably, poor.Philadelphia's awareness and interest in historical preservation goes back to the early part of the 19th century, when the City purchased the old State House -- Independence Hall -- to prevent its demolition. Ever since and all at once, we've proven to be careful stewards of architectural heritage, habitual backward-thinkers stuck in the past, neglectful of worthy jewels, sloppy and imprecise renovators, forward-minded soldiers of Modernism, and mean-spirited, eleventh hour bunglers. John Gallery, the city's first housing director and present executive director of the Preservation Alliance of Greater Philadelphia, underscores the schizophrenia. He estimates that this past decade while NTI wreaked havoc on the industrial streetscape, the Civic Center and the buildings in the way of the Convention Center expansion were demolished without public debate, and acres of row houses were lost to poverty and lack of resources, $3 billion in major preservation was completed. But Gallery, who has had a hand in much urban policy in Philadelphia these last 35 years, and who still retains a New England accent, says it's time for Philadelphia to develop and implement a preservation plan. Only a plan, with a careful historic context statement and a comprehensive survey of neighborhoods, would properly allow officials and community members to make an informed decision about a project like Wayne Junction. Does the station support an historical theme? Is there a context for preservation in Nicetown/Lower Germantown? Are there other station headhouses in Septa's inventory of equal or greater historic value? The Preservation Alliance, along with its partners the Historical Commission, Penn's School of Design's graduate program in Historic Preservation, and the Planning Commission, have reached the second phase of a pre-plan study. This phase is funded in part by the William Penn Foundation and Heritage Philadelphia (a grant of $100,000 was just awarded), with additional funding sought from the Barra Foundation. In a short time, a steering committee will be formed and the Alliance will expand the project's realm of community partners. An historic context statement, which Gallery says is critical to a meaningful plan, will be devised and associated historic themes developed. Frankford will serve as a test neighborhood for the development of survey methodology. Historic preservation, so fraught with nuance (for a review of some of the intangibles in preservation, see a Philadelphia-esque story in today's New York Times), is never on sure political footing. Gallery says his greatest present concern is that the Historic Commission is not adequately funded. Beyond that, he'd like to expand the number of city historic districts -- Parkside has been proposed -- but even those lack teeth. He says Diamond Street in North Philadelphia, an historic district that includes the Church of the Advocate, is literally falling down. Only some 20,000 buildings in Philadelphia are protected; still, neighbors across the city fearful of gentrification oppose historic designation. Meanwhile, the greatest preservation crisis we face, the slow, steady deterioration of row house blocks across much of the city, continues unabated without a policy solution. One of the shortcomings of the Wayne Junction project is caused by Septa's infamous bureaucratic divisions. Acchione is charged with repairing the station. Someone else is in charge of Regional Rail scheduling (does it make sense to run more trains to and from a revamped station?), someone else oversees bus operations (is there a strategy to move riders off the slow 23 and onto fast regional rail?), someone else manages the three neighboring maintenance yards, someone else promotions and advertising, someone else station maintenance (Wayne Junction is notoriously dirty and there is no maintenance plan for the station once it is renovated), someone else again ticket office operations. All of these separate functions inform the overall project, but in the community's hopeful scenario each function would follow a larger vision for the station as an economic engine. "This is not pie-in-sky," insists Stephen Hague, but if vision -- and not bureaucratic division -- is to lead it will require more than a philosophy change at Septa. A renovated station will be a nice community asset. Ridership at the station will increase (it already has -- by 27% 2005-2007). But as an envisioned economic engine, Wayne Junction ought to be the gateway to historic Germantown -- for its richness of themes and sites one of the most compelling historic destinations in America. Once that vision is articulated the question of whether to save the station headhouse doesn't have to wait for a preservation plan in order to be answered. The still-used 1885 Glen Echo Mills just behind the station gains protection; the evocative and shuttered Loudoun mansion, just above the mill, becomes the Germantown historical interpretive center; and the massive abandoned industrial complex at 18th, Windrim, and West Courtland Streets that was once in part a gun factory and is now a community trouble spot, is razed to create a visual and pedestrian connection between the station and Stenton.  Glen Echo Mills. For more on this site, visit Workshop of the World. Then, as one reader recently proposed, return the classic trolley to the 23 by dividing the line into sections with already built-in turnarounds. In this case a Germantown section meets the North Philly-Center City section at Wayne Junction reinforcing the train station's hub status. The reader, who requested anonymity, recommends returning the classic PTC trolley to the Germantown section, extending preservation into the realm of tourist-friendly experience. Acchione says that he is hampered by limited resources -- despite the promise of dedicated funding, the Market Street Elevated reconstruction continues past schedule and over budget. The El may or may not be the ogre in the room but Acchione's point is valid; under current funding formulas visionary ideas and ambitious preservation plans can't be implemented. This might cause us to examine the way we'd like local government to work. John Gallery wants preservation to provide a frame for neighborhood renewal. He doesn't use far-fetched economic analysis to qualify the success of preservation rather he would argue that Philadelphia's greatest and most unique asset is its urban fabric. It's irreplaceable and therefore needs to be protected. We might call his a capital intensive approach to urban policy. Everyone benefits when the physical environment of the city is nurtured. Large projects employ lots of people; a more attractive city attracts smarter and better educated people. The above-vision for historic Germantown becomes possible with a capital intensive approach. Starting in the 1960s, with economic and racial justice as municipal goals, city planners began to question the sustainability of this approach. Resources ought to be invested in people instead -- and the notion of human capital was invented. Educate, train, and nurture people, raise their income-potential, and they'll make the city better. This notion held sway among academics well into the 1990s. Mayor Rendell understood the drawback of this approach: it failed to produce physical symbols -- landmarks -- of change and so he preferred to build (repeating the strategy at the state level as Governor). Now, a decade into a building boom, we're enamored again of capital-intensive physical projects that promise to make the city more fun and attractive to investors, businesses, and tourists. Mayor Nutter is faced with more ideas for projects than he could build with unlimited resources in a 100 year term. But Nutter's resources are severely limited, in part because we still expect local government to follow both strategies. Thus his budget increases funding for Fairmount Park (capital) and Community College of Philadelphia (human capital). And there are many observers, including my longtime friend Len Ellis, who support a much stronger human capital approach. Ellis wrote three weeks ago in the Daily News that Nutter's education goals fall far short of what it will take to increase Philadelphia's income potential. Noting that Philadelphia ranks 92 of the largest 100 cities in college attainment, he says the best thing we can do for Philadelphia is get more people to go to and graduate from college. A smarter workforce will attract better firms.  Public sector spending follows the dual-strategy approach. Philadelphia's proposed 2006 $3.5 billion operating budget designated $830 million for social service

programs. (Approximately $2 billion, 58% of the 2006 budget, was to be spent on salary, pensions, and benefits, arguably a stabilizing investment in human capital.)

Among the city's Capital Program Office ($50+million), the Airport ($100 million), and Septa ($426 million), Philadelphia spends less than $600 million on capital

projects each year, leading us to believe that if there is an imbalance it favors the human capital approach (the state of our sidewalks might offer useful evidence).

Public sector spending follows the dual-strategy approach. Philadelphia's proposed 2006 $3.5 billion operating budget designated $830 million for social service

programs. (Approximately $2 billion, 58% of the 2006 budget, was to be spent on salary, pensions, and benefits, arguably a stabilizing investment in human capital.)

Among the city's Capital Program Office ($50+million), the Airport ($100 million), and Septa ($426 million), Philadelphia spends less than $600 million on capital

projects each year, leading us to believe that if there is an imbalance it favors the human capital approach (the state of our sidewalks might offer useful evidence).

But no true comparison between human services and capital is possible; much of both types of spending is hidden throughout the budget. The two approaches employ distinct sources of funds -- tax revenue for human services and bond revenue for capital -- meaning that it's impossible to borrow from one approach to bolster the other. Government programs are also vertically connected federal-state-local, so no city controls its revenue or its spending, which is shaped in part by mandates. Nor can we sincerely imagine abandoning either one. So we'll have to look ahead to a change in federal government philosophy, to one that would exchange lower taxes for higher quality of life. It has been ages since Washington took a leadership roll addressing the nation's infrastructure. Some prognosticators think global warming might change that, in which case dreams about Wayne Junction won't seem so pie-in-the-sky. –Nathaniel Popkin nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com For more on The Possible City, please see HERE. For Nathaniel Popkin archives, please see HERE, or visit his web site HERE. |

|

• 1 Apr 08: "Recess/Re-assess • 7 Mar 08: "One-City Art Movement, Open to Everyone • 24 Feb 08: "Too late for the streetscape? • 15 Feb 08: "It really could be something." • 18 Jan 08: Estuary of Dreams • 11 Jan 08: More than shelter • 10 Jan 08: Nature's balance • 6 Dec 07: Snake uprising • 4 Dec 07: A Junction that ought to be • 6 Nov 07: Around the Mulberry Tree we go • 29 Oct 07: Wondering about wandering • 5 Oct 07: No other way • 21 Sept 07: Here is the Possible City |