|

Forgotten Philadelphia: Lost Architecture of the Quaker City, by Thomas H. Keels

Temple University Press, 2007, 320 pages

Reviewed by Nathaniel Popkin

I spent some time in the Northern Liberties this week, walking some of the narrow streets and alleyways between Third and Fifth Streets for the first time in a while.

It

still feels just a little like a lost world: amidst the dozens of wildly disparate and somewhat overblown new row houses morning glories climb the signposts and cats

dart

and late season begonias -- their leaves parched and therefore the color of sea glass, their flowers drained to barely pink and yellow speckled -- linger on, insistent

and

therefore ravishing. Giant Paulownia leaves are underfoot -- they've landed on a patch of luminescent blue brick paving, that strange bejeweled -- glazed, certainly --

cobblestone you find also on the 1400 block of Addison Street. Out beyond are weeds, frogs, I imagine the rusting carcass of a Citroën -- maybe in five years all

this

will be gone, this land of Indians and settlers, barkeeps and smelters, paved back and properly tamed. If you've lived for a while on St. John Neumann or Orianna or

Myrtle

or Leithgow it must be unsettling to watch the charm disappear.

I spent some time in the Northern Liberties this week, walking some of the narrow streets and alleyways between Third and Fifth Streets for the first time in a while.

It

still feels just a little like a lost world: amidst the dozens of wildly disparate and somewhat overblown new row houses morning glories climb the signposts and cats

dart

and late season begonias -- their leaves parched and therefore the color of sea glass, their flowers drained to barely pink and yellow speckled -- linger on, insistent

and

therefore ravishing. Giant Paulownia leaves are underfoot -- they've landed on a patch of luminescent blue brick paving, that strange bejeweled -- glazed, certainly --

cobblestone you find also on the 1400 block of Addison Street. Out beyond are weeds, frogs, I imagine the rusting carcass of a Citroën -- maybe in five years all

this

will be gone, this land of Indians and settlers, barkeeps and smelters, paved back and properly tamed. If you've lived for a while on St. John Neumann or Orianna or

Myrtle

or Leithgow it must be unsettling to watch the charm disappear.

I stopped by the new offices of Erdy-McHenry Architecture, in a blank-walled former auto-body shop, until last year filled floor to ceiling with cars and parts. Their

touch

is deft, solid, sure -- and now the vaulted space makes you feel as if it had always wished to be the atelier of some serious-minded architect. On Lawrence Street,

with its

run of nearly-perfect worker housing between St. John Neumann and George, I visited with Karl Olsen, the painter and former blacksmith, who with his wife Sara, herself

a

metal-worker, turned a former diaper factory into a house, courtyard, and studio. The steel trusses from the old industrial roof still fly over head; a bitchy rabbit

hops

along underfoot; grape vines and wisteria battle for territory. Karl took me down the block to meet Sal and Duncan Buell, who occupy a three-story former horse barn.

Duncan made me coffee and I sat in the magnificence of their living room. Sal opened the double barn doors and there danced the gold dome of the Ukrainian cathedral

just

beyond, and I listened intently to their stories -- of Sal's '67 Beetle, of the raceway at Philadelphia Park, of Duncan's exhausting, exhilarating time working for

Louis

Kahn.

For the third time in a just a few days, I was moved by this extraordinary act of adaptation. What it means to be a Philadelphian is to live, without quite

obliterating it,

inside someone else's dream. Karl does -- his courtyard with Sara's tall red cannas is dotted with the remains of that old factory; its door is his. Most of us have

to

walk through someone else's door -- which is why it makes sense to begin a conversation on the Possible City with a review of a book called Forgotten

Philadelphia.

I'm not advising we start by looking back, merely acknowledging that by isolating the tension between the weight of the past and the vital imperative to move forward,

this

book by the writer Thomas Keels is valuable, fascinating, and prescient. Indeed, Keels isn't reveling in some mythic past. Rather he's describing the power of the

desire

to build anew: how it forms, spreads, wins out -- or often enough gets lost, compromised, or forgotten. Along with histories and pictures of some 200 Philadelphia

buildings

torn down, Keels leaves us with a chapter on "Projected Philadelphia," in which he imagines, you guessed it, the Possible City. (Keels revels too in Louis Kahn,

calling

this imagined place the "City of Availabilities.")

The more I write about Philadelphia, the more I'm stuck by the depth, love, and expertise of her bards. Keels, like Beth Kephart, the author of Flow, the

lyrical

autobiography of the Schuylkill, and Gary Nash, who wrote 2002's First City, has found a new way to rekindle this city's history without telling straightforward

historical narrative. (First City is the history of how history has been told -- and an invaluable cultural resource.) Though it is a beautifully-produced,

visually

elegant work, Forgotten Philadelphia's strength is its narrative awareness -- this is a painstakingly-researched book to read through.

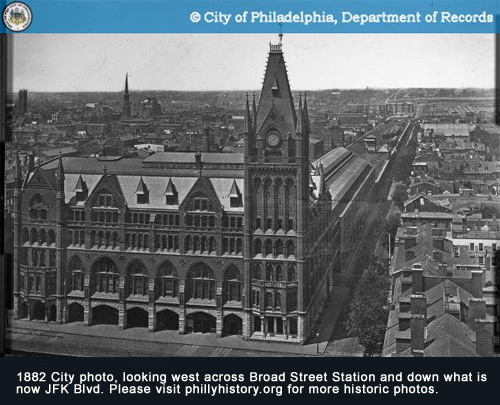

Keels introduces the reader to the tension inherent in the changing city by telling us the story of the 1952 demolition of Frank Furness' Broad Street Station. Through

this

one telling example we come to immediately understand the writer's handle on the thrill and melancholy of demolition.

Even though an agreement to demolish Broad Street Station had been in place since 1925, the destruction of the building (postponed by the Depression and

World

War II) took countless Philadelphians by surprise, much like the death of an elderly but vital aunt whom one had assumed would live forever. Philadelphians' sorrow

transcended the loss of a familiar, lifelong locale, the scene of countless memorable meetings, arrivals, and departures.

Keels goes on to mete out the politics, economics, and cultural significance of the $157,500 demolition of the nation's busiest train terminal, grief versus faith, a

pattern

he says has been repeated throughout the city's history. A minor critique I have is the way Keels, so fond of the clarity of this tension, uses the rest of the

introduction

to sell the idea of his book. Some of it sounds like it came straight out of the pitch he used to find a publisher.

But once the author gets into his subject-matter, the reader feels as if he is in good hands. From the circa 1666 Swedish block house -- "common Scandinavian

structure" --

to the old Liberty Bell Pavilion, Keels demonstrates the thoroughness of his research. Here, with incisive detail and a firm understanding of natural history, he tells

us

about the Blue Anchor Tavern, built circa 1682 (perhaps 1671), demolished 1828.

Besides being "Victualler and Tappers of strong drink" with sturgeon and sea turtle on its menu, the Blue Anchor became Philadelphia's commercial exchange

and

transportation hub. Watson called the tavern "the proper key of the city, to which all new-comers resorted." At the Blue anchor, goods were traded from all ships

anchored

in the Dock. Ferries carried passengers to New Jersey, to Windmill Island where a windmill ground their grain, and across Dock Street to Society Hill. Farmers tied

their

boats to the tree lining the Swamp and sold their produce to local housewives.

A 1691 citizen's petition asking that the Blue Anchor's landing be made a free harbor signified its pivotal role in early Philadelphia. Penn obliged by designating the

Blue

Anchor wharf one of two permanent landings in his 1701 city charter. By this time, unfortunately, Dock Creek was changing from open water to an open sewer, polluted by

the

waste of nearby tanneries, lumberyards, and slaughterhouses. (Between 1767 and 1784 the entire creek was covered over to create Dock Street.)

Keels enjoys telling us about the rudimentary, curious, ornate, misunderstood, absurd -- the book's candy -- and so we have cave dwellings along Front Street, the

unused

Presidential Mansion, the Marble Arcade, Moyamensing Prison, the Phil-Ellena mansion, Jayne's, Kiralfy's Alhambra Palace, the Floating Church of the Redeemer ("Even the

most

zealous missionary, however, has to concede the logistical difficulties of a floating church."), the Forum of the Founders, the Bulletin Building, and Lubinville,

Siegmund

Lubin's groundbreaking movie studio at 20th and Indiana.

But the meat is the ideas implicit in the design and demolition of all these structures. Take, for example, the Arcade Building, built by Frank Furness to mimic

Milan's

Galleria Vittorio Emanuele. Keels tells us the spatial problem the owner of the building, Alexander Cassatt, needed to address, the design compromise that resulted in

a

"monumental portal," and the building's ultimate aging, falling out of taste, and demolition, in 1969. "Modern Philadelphians," Keels says in the introduction, "wonder

how

their forefathers could have been so shortsighted or self-centered as to permit the loss of such relics." Keels tells us why: the Arcade Building was demolished to

create

Dilworth Plaza, the vast public space just west of City Hall. While Dilworth Plaza has never been properly used and in its turn is glaringly ready for demolition, can

you

argue with the instinct to give City Hall a foreground?

The essay on Tasker Homes, built in 1940 and demolished in 2001, is a telling example of how ideas get twisted in reality. The project was designed in the

International

Style, loaded with intentional design elements such as community-building courtyards, a community center, square and school (Audenried), all rationally distributed

throughout. Though essentially treeless when it opened, the units were a modern respite from the Depression. And yet this relatively ground-breaking development

quickly

fell out of favor and into chaos and disrepair. The Schuylkill Expressway, racism, and the erosion of the public sector effectively battered the ideals so that when it

came

down six years ago a great sign of relief was heard across the city.

Intent, ideas, hope: perhaps these count for something, but the great melancholy of this book is the recognition of wasted energy, the sorrow of dreams washed away.

This is

no more so than in the section on Projected Philadelphia. Here is the reminder that we've all been here before, attempting to reform and reinvent this city. Are we

too

destined to destroy what we ought to save, discard what we ought to build? How do we plan not just for today but for the city of tomorrow? (Keels reminds the reader

of the

difficulty even in projecting population -- that in the 1950s, planners were imagining a city of three million, not half that.) A reasonable place to start might be

with

ideas that seem to endure, demolition or not. The three I keep coming back to -- they vary in scale and ambition -- the role of exuberant architecture, the need for

even

temporary structures for play and recreation, and the scale of ambition. We still wish to make our mark. Keels quotes the architectural historian George Tatum,

"Because

they were not afraid of new ideas, whether in the field of politics, social reform, or the arts, Philadelphians were among the first to try new architectural forms and

theories. They produced the most advanced hospitals, the most progressive prisons, several of the most ambitious churches, and some of the earliest and most beautiful

municipal parks. Their bridges were longer, wider, and deeper than others of their day."

–Nathaniel Popkin

nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com

* * *

Tom Keels appears at Borders Bookstore at Broad & Chestnut tonight (Tuesday, September 25), and then on Wednesday, November 9 to sign and discuss Forgotten

Philadelphia.

For more on Forgotten Philadelphia, visit your local book shop -- how about Joseph Fox Book Shop or

Robin's Bookstore? |