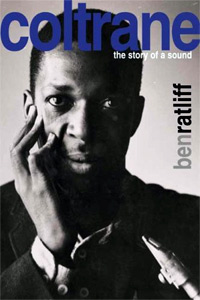

Coltrane: The story of a sound, by Ben Ratliff

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2007, 217 pages

ISBN-13:978-0-374-12606-3

Reviewed by Nathaniel Popkin

It may be sacrilege to place John Coltrane and Dick Clark in the same sentence, but then I've just done it. Really, it's Philadelphia, as any reasonably complex

city, that puts divergent bodies in motion. In the spring of 1957, as Louis Kahn, with Ian McHarg as lead landscape architect, was preparing the initial design

for the Richards Medical Research Building at Penn (the first designs were presented in June), Clark, sensing opportunity, began pushing hard for ABC-TV to

broadcast Bandstand nationally, which they did beginning in August. It may be even more provocative to place Lou Kahn and Clark together, but for each man

that spring West Philly was his oyster. Kahn, who composed architecture as a form of music, saw the Penn project as a breakthrough multi-disciplinary approach to

medicine (Penn and Kahn apparently were avant-garde: now 50 years later the concept is embraced in Jefferson's Hamilton Building). Clark, the false naïf,

saw gold in teenage longing -- and disturbing talent in the filth of South Philly.

It may be sacrilege to place John Coltrane and Dick Clark in the same sentence, but then I've just done it. Really, it's Philadelphia, as any reasonably complex

city, that puts divergent bodies in motion. In the spring of 1957, as Louis Kahn, with Ian McHarg as lead landscape architect, was preparing the initial design

for the Richards Medical Research Building at Penn (the first designs were presented in June), Clark, sensing opportunity, began pushing hard for ABC-TV to

broadcast Bandstand nationally, which they did beginning in August. It may be even more provocative to place Lou Kahn and Clark together, but for each man

that spring West Philly was his oyster. Kahn, who composed architecture as a form of music, saw the Penn project as a breakthrough multi-disciplinary approach to

medicine (Penn and Kahn apparently were avant-garde: now 50 years later the concept is embraced in Jefferson's Hamilton Building). Clark, the false naïf,

saw gold in teenage longing -- and disturbing talent in the filth of South Philly.

Having already been invited in and discharged by Miles Davis, Coltrane came home to 33rd Street in the Strawberry Mansion section of North Philadelphia (his family had moved there from North

Carolina when Coltrane was 16), to dry out. As much of the jazz world, he was a heroin addict. And heroin was about to wreck his career. Inside that house

facing Fairmount Park he went cold turkey.

As Ben Ratliff, the New York Times jazz critic, explains in the nearly-perfect Coltrane: The story of a sound, "his periods of greatest clarity and

ambition came when he was not only off drugs and alcohol but emotionally focused." In fact, Coltrane accelerated starting that spring. Thelonius Monk hired him

to join his quartet, then Davis again before the tenor saxophonist formed his own quartet in 1959. In the six years that followed, Coltrane formed his sound --

and that was before the last two years of his life when having exhausted his horn, he leapt fully out of bounds.

Yet Ratliff's book isn't traditional hagiography. In the introduction he says it's more critique than biography, but I see it as something more akin to the music

itself. Here, Ratliff describes Coltrane and Wayne Shorter experimenting.

Later, they talked about improvising and language, and how it might be ideal to start a sentence in the middle, then travel backward and forward, toward both the

subject and the predicate, simultaneously.

This is just the author's challenge in describing the evolution of a sound. It can't be told temporally or even thematically, so Ratliff masterfully does both,

as if he's playing one with the left hand, the other with the right. This is a wise and fluid book, dotted, as is any story of jazz, with people (so many names),

dates, concerts, and clubs. Nothing lasts long and history is made in an instant. What I like so much is Ratliff's range -- from Ravel to Stravinsky, Robert

Lowell to Amiri Baraka, Jane Jacobs to Kant, Akbar Ali Khan to Mantle and Maris, Henry Miller, and the Bay of Pigs -- while never resorting to cliché --

not once is "cat" used to describe a jazz figure. He doesn't employ these people as mere context either, rather to illuminate the essence of his subject, who was

at once the symbol of Black Power and a hungry polyglot in search of universal theory.

He had peace, and time to practice continually, on many instruments: besides tenor and soprano saxophone in the house, he had Eric Dolphy's flutes, bagpipes, a

harp, various drums, and an acoustic guitar. He was still using charts and graphs, based on math and astrology and architecture, to inspire composition; he had

even found ways to derive song from the shape of a cathedral.

(It's instructive to think about Coltrane making architecture from music and Kahn making music from architecture -- and both men drawn simultaneously to south

Asia.) I fell for Coltrane as a college student living at 42nd and Walnut, spending hours listening to those orange and black Impulse CDs in the music store that

was in the basement of Houston Hall. A Love Supreme filled the tall ceilings of my room and haunted my nights. But I couldn't have told you why. "The

point to be drawn from this," Ratliff says as if to answer, "is that a musician can project his will on anything; harmonic restrictions and complicated structure

can coexist with simplicity and openness; lyricism can coexist with ferocity." Exactly. Now I listen anew. What a gift.

Ratliff spends Part Two of his book parsing Coltrane's influence. His death in 1967 from liver cancer came quickly; few realized he had been sick. Jazz

stumbled, still seeking direction, and Coltrane, ever analyzed, is often misunderstood. Ratliff is setting things straight (in part by wreaking havoc).

But in my view one of the most useful and overriding ways to comprehend the arc of Coltrane's work, one that contains significance of jazz now, is to notice how

much he could use of what was going on around him in music. He was hawklike toward arrivals to his world, immediately curious about how they could serve his own

ends, and how he could serve theirs.

Some -- many, perhaps -- of those arrivals latched onto him here. McCoy Tyner, the pianist, is the most famous. Tyner spent hours on 33rd Street; Coltrane

offered him a job early, well before he'd organized his own quartet. Rashied Ali, a stalwart of the Philly scene, would sit in Fairmount Park in the late 1950s

and listen while Coltrane practiced across the street, on the third floor.

Back from WWII, Coltrane used the GI Bill to attend the Granoff School at 17th and Chestnut. Isadore Granoff, who died in 2000, was a Jewish immigrant from the

Ukraine who began himself as a Philly teenager giving violin lessons. Coltrane's capacity to make use -- absorb and reinterpret -- reminds me of a great city on

all cylinders: it's hungry for all the talent it can get.

–Nathaniel Popkin

nathaniel.popkin@gmail.com

For more on The Possible City, please see HERE.

For Nathaniel Popkin archives, please see HERE, or visit his web site HERE.

* * *

B Love Note: John Coltrane was one of my earliest Philadelphia inspirations as well. The Impulse Years series was in heavy rotation in my latter days in

college, just before it was stolen with a tower of CDs, a Sony Playstation (first version), a VCR and a camera. (It was college, what can ya do?)

Anyway, Coltrane. Jazz is often so complex that casual music fans just don't bother with it, and even the most dedicated music fans sometimes hit a brick wall

with the likes of On the Corner by Miles Davis and Coltrane's Meditations. But the folks who get their first taste of jazz through Coltrane often

find themselves at "My Favorite Things".

Where "Take the A-Train" might be the "Like a Rolling Stone" of the jazz scene, "My Favorite Things" could be considered the Hendrix version of "All Along the

Watchtower" in that it took an existing song (Rodgers & Hammerstein's 1959 song from the Broadway production The Sound of Music) and perfected it. On the whole,

Julie Andrews' performance of the song in the 1965 movie may be more recognized, but the 1960 recording by Coltrane's quartet (including McCoy Tyner, Elvin Jones

and Steve Davis) and its subsequent renditions are Coltrane's signature number, especially this time of year.

All this in mind, let's heat up some mulled wine, crank this yank on YouTube and get on down to My Favorite Things from Germany in 1961 with Coltrane, Tyner,

Dolphy, Jones and Workman.

–B Love

|